Researchers will test convalescent blood plasma therapy in two nationwide trials to determine its effectiveness in treating COVID-19 patients

Johns Hopkins researchers have received $35 million in funding from the U.S. Department of Defense for two nationwide clinical trials to test the effectiveness of a convalescent blood plasma outpatient treatment that may help COVID-19 patients’ immune systems fight the virus.

The randomized double blind trials totaling 1,100 people will be conducted at over 20 ambulatory clinics in medical centers across the U.S., including the Navajo Nation, and will help researchers determine whether convalescent blood plasma therapy—a transfusion of a blood product from COVID-19 survivors that contains antibodies—can effectively be used to treat people in the early stage of COVID-19 illness or prevent the infection in those at high risk of exposure to the virus at their home or jobs.

Currently, there are no FDA-approved vaccines to prevent infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes COVID-19, nor approved treatments for the illness in its earliest stage. There are also no outpatient therapies to prevent hospitalization or death.

“This is a story of great synergy between researchers and institutions to carry out important studies that will inform our nation and the world on how effective plasma can be to prevent COVID-19 and to treat early disease,” says Arturo Casadevall, a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor who holds joint appointments in Bloomberg School of Public Health and School of Medicine. To initiate the clinical trial, Casadevall and his colleagues assembled a broad collaboration of investigators at Johns Hopkins and at participating medical centers across the U.S.

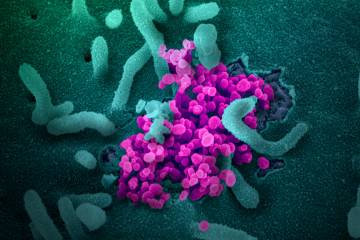

Image caption:Shmuel Shoham from Johns Hopkins Medicine and David Sullivan from the Bloomberg School of Public Health discuss the blood plasma clinical trials and their potential applications.

Leaders of the trials include Casadevall and his colleagues Shmuel Shoham, associate professor of medicine at School of Medicine, David Sullivan, professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the Bloomberg School of Public Health, and Daniel Hanley, director for multisite clinical trials in the Institute for Clinical and Translational Research at the School of Medicine.

“Blood plasma therapy may have the most potential in providing immediate immunity to people at high risk of COVID-19 exposure and treating COVID-19 early to prevent hospitalization or death,” says Sullivan. “For definitive proof of this, we need a rigorous randomized clinical study to evaluate it.”

The prevention trial will include 500 people who have been exposed to COVID-19 in their home or at work as health care providers. The companion trial will have another 600 participants who have early COVID-19 disease, meaning they are within eight days of their first symptoms but are not sick enough to be in a hospital. All participants will be over age 18. The researchers aim to complete recruitment of participants to the trial in early fall 2020.

Convalescent blood plasma therapy involves transfusing a portion of blood called plasma from people who have recovered from the virus. When separated from red and white blood cells and platelets in the blood, plasma is the yellow-tinged liquid that includes proteins called antibodies, which glom on to foreign substances such as viruses and either mark them for destruction by the immune system or disrupt a virus’ ability to multiply and grow.

Physicians have used the treatment for severe diseases in hospitals for more than a century, often during epidemics such as the influenza pandemic of 1918 and the more recent outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in 2003. Laboratory experiments in the past have shown that the therapy neutralizes many viruses. However, the treatment is often used in the chaotic phases of a crisis without the rigors of a large clinical trial.

There is very little clinical data proving the effectiveness of using the therapy in outpatient clinics, according to the researchers. Currently, only hospitalized patients have access to any type of therapy for COVID-19.

“Because plasma from recovering patients is widely available, it may be a rapid low-cost treatment of major value in early stages of epidemics. A randomized trial is needed to clearly demonstrate these historical and laboratory proven benefits,” says Hanley.

ALSO SEE

The blood plasma used in these trials is being collected from many organizations, including the New York Blood Center and the American Red Cross. One donor can provide plasma for up to three people. Trial participants will receive one IV infusion of the plasma at an outpatient facility, which usually takes about an hour.

As part of the trials, participants with COVID-19 will be monitored over four weeks to determine the course of the disease and its severity. Participants who have been exposed to the virus will be evaluated over four weeks for development of COVID-19 infection, including symptom checks and laboratory testing for the virus and antibodies. The researchers will examine the long-term immunity of both groups at three months after infusion with convalescent plasma.

From the trials, Shoham says, the researchers hope to learn if blood plasma can prevent infection or squash it where it begins. “There are also biological implications,” he says, adding that blood plasma therapy could expand treatment options for viral diseases. “We’re reviving an old approach to fight pathogens, and it may be useful for other viruses or parasites such as malaria.”

Johns Hopkins research into convalescent blood plasma therapy was previously funded by $3 million from a Bloomberg Philanthropies gift and $1 million from the state of Maryland. Johns Hopkins also received a $1 million award supplement from the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Additionally, the researchers used the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Trial Innovation Network and the National COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma Project at Michigan State University to develop interest in the trial among participating centers.

Jason Roos, deputy joint program executive officer for chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear defense, says, “We’ve seen that convalescent plasma can benefit patients suffering from some of the worst effects of COVID-19. The JPEO-CBRND is excited to be working with Johns Hopkins University to determine whether that same plasma could help protect our Joint Forces from COVID-19, either by preventing infection altogether or drastically reducing their symptoms. Those types of beneficial outcomes would help us make sure our servicemen and women stay healthy so they can complete their mission.”

Other key faculty supporting this project include virologists Andy Pekosz and Sabra Klein of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and transfusion medicine experts Evan Bloch and Aaron Tobian of the School of Medicine.